Mapping realities: how a new risk assessment approach aims to drive critical climate planning and ‘difficult’ conversations across the basin

news

Published 12 Dec 2024

Written by Ralph Johnstone

When it comes to long-term climate change in the Murray-Darling Basin, the statistics are shocking – if not completely crippling. Flows from the vital Goulburn-Broken catchment into the Murray River declining 30% by 2050. Mean temperatures rising by 1.5 to 2.5°C, evaporation by 10-15%. Heatwaves intensifying, rainfall plummeting. Annual flows in the Lower Murrumbidgee, already down 50%, contracting by a further 10-25%.

The problem is that all these figures are for giant catchments, if not the entire 1 million square-kilometre basin. And they’ve been quoted so many times, for many they’ve begun to lose their meaning.

“If you’re trying to understand which climate conditions could cause water storages or distribution systems to fail, these figures won’t be of much use to you,” says Holger Maier, Professor of Environmental Engineering at the University of Adelaide, and one of our leading thinkers on the risks to basin infrastructure posed by climate change.

While there’s an avalanche of data confirming the mounting impacts of climate change on temperatures, rainfall and river flows across the basin, very little of this is of direct use to the farmers, irrigators, water systems managers, and communities whose livelihoods stand the most to lose from these changes. For the environmental engineers and scientists who’ve been studying these phenomena for years, it’s clear that a new approach is needed to engage people in the risk assessment process – and make these assessments more relevant and actionable in their lives.

In September, a project funded by One Basin CRC and led by Holger and his University of Melbourne counterpart, Avril Horne, in partnership with the Murray Darling Basin Authority, set out to rectify this glaring gap in water systems planning. Over the next three years, the project will develop a series of simple assessment tools to help water users analyse long-term climate scenarios in their localities, ‘stress test’ different aspects of their operations and water use practices, and identify potential adaptation strategies. By working directly with end users, the project aims to inspire a cultural shift away from a focus on understanding the way the climate might change to more practical analyses that will help people gauge which elements of their operations are sustainable, which are most at risk – and what they can potentially change to make a difference.

The project will bring together the environmental engineering and modelling experience of teams at the University of Adelaide and the University of Melbourne with the social science expertise of researchers at the Australian National University to better understand people’s values, stress test how well these values can be maintained under changed conditions, and explore the potential impacts of various adaptation strategies.

In the same week that the ‘Putting People at the Centre’ project had its first full team meeting in late November, its methodology was also shared by Holger at the 2024 Hydrology and Water Resources Symposium, as well as by Avril and her colleague Andrew John through a One Basin/Australian Water School webinar attended by 300 people.

“We want to give people the ability to explore how their systems will perform under different conditions, to help them make the best decisions they can,” explains Holger. “At the moment, projections vary significantly based on a range of assumptions and scenarios, and people are being paralysed by their inability to connect the huge range of information out there to the things that really matter to them. We know that change is coming. We want to help people analyse and study how much flexibility exists in their systems, so they can gauge the tipping points and manage their risks better.”

Information for action

As its name suggests, Putting People at the Centre will use stress-testing as the baseline for a series of tools that ‘non-techie people’ can use to calculate the risks facing their water systems and supplies under different conditions – as part of a broader process of discussing, devising, and testing different adaptation strategies to reduce those risks.

“We’re starting by thinking about the things that people care about, and then figuring out what needs to be included in a model representing those things, and the risks from an uncertain climate future,” says Avril, a water policy specialist who’s spent much of the past decade studying adaptive water management under uncertainty.

“We have a lot of experience from previous projects, such as the current CRC quickstart project looking at stress testing water allocations. We can build on these techniques and aim to make the outputs as accessible to use as possible – and the methods transferable to other applications.”

Because of the entrenched nature of current climate risk assessments – and the need for a longer-term cultural shift – it is hoped that the initial three-year timeframe of People at the Centre will be extended beyond 2026.

In its first year, the project will liaise with stakeholders and begin testing its risk assessment approach through four regional case studies with local catchment management authorities: from irrigated agriculture and environmental flows with the Murraylands and Riverland Landscape Board in the southern basin; to community priorities with the Goulburn-Broken Catchment Management Authority; and the impact of bushfires on water quality and irrigated agriculture with the North East Catchment Management Authority. In the second and third years, the researchers will work with regional stakeholders to refine the tools to better measure the impacts of specific ‘climate stressors’ on their lives – and how they can use these findings to develop and test potential adaptation strategies to improve their water efficiency, crop choices, and other land and river management practices.

Finding the ‘sweet spot’

In South Australia’s Riverland, Australia’s largest wine-growing region, an extremely dry winter this year led to a string of September frosts which decimated many vines that had ripened early because of high temperatures. It is these types of vulnerabilities, which are generally missed using current broad-brush approaches to climate risk assessment, that the People at the Centre project is endeavouring to uncover and model.

Michael Cutting, head of sustainable agriculture at the Murraylands and Riverland Landscape Board (MRLB), believes that the project has the potential to directly support the decision-making of 3,000 irrigators in the Riverland – especially when it comes to balancing the maintenance of productivity with their climate response.

“We so often get caught up with the recovery of water, but if you’re trying to fight climate change challenges, it comes back to how hard can we push the system,” says Michael. “We need to find the sweet spot, the balance between reducing our water use and optimising our production. There’s no shortage of information: we have some good examples from the Millennium Drought, but often they’re not presented in a visual or user-friendly form that growers can use to make that information actionable.”

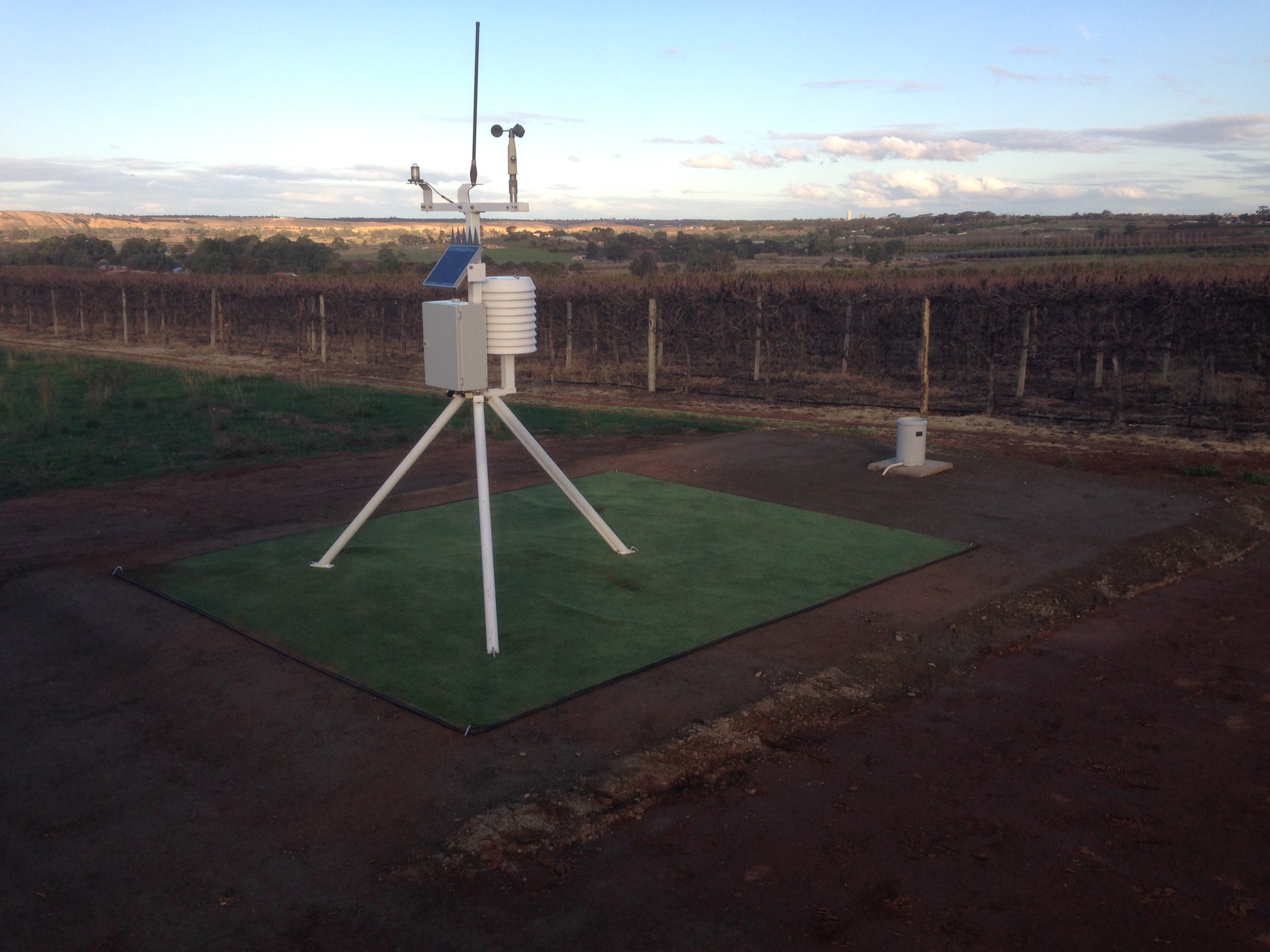

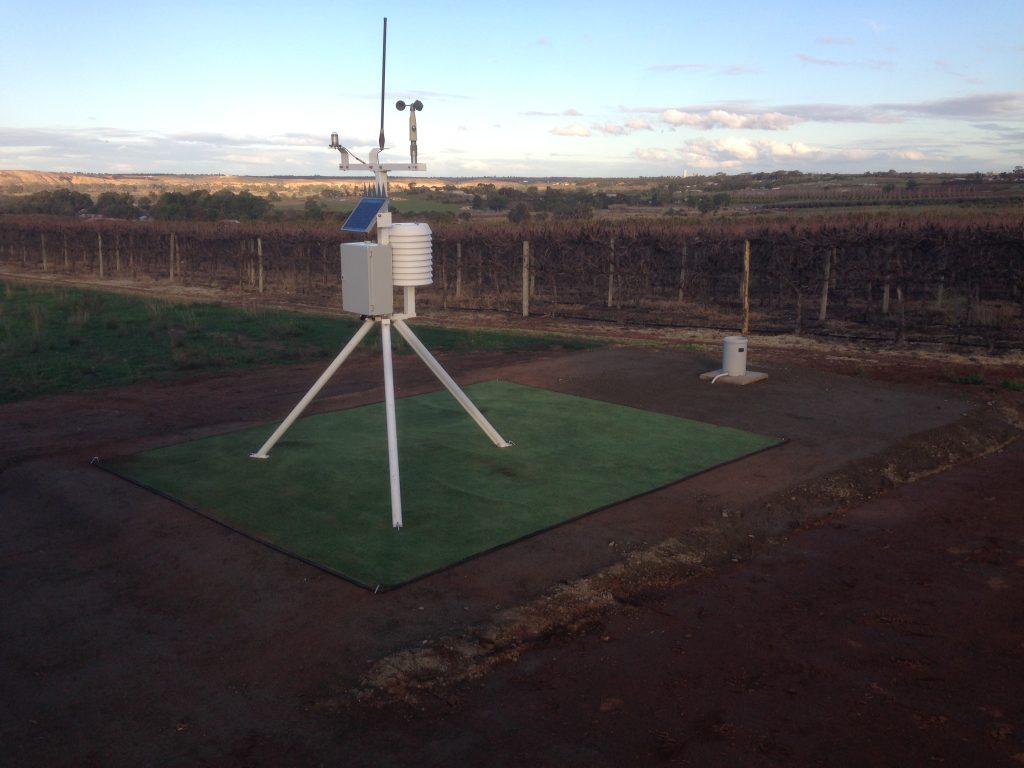

Over the past 20 years, grape growers have developed many and varied strategies for coping with high temperatures – from breeding drought-resistant and warmer-weather varieties, to sophisticated ‘dual irrigation’ systems that switch between production and cooling modes. MRLB recently installed instruments at several vineyards to measure the success of these systems in countering extreme temperatures, and to evaluate their cost effectiveness.

“This kind of quantifiable data will feed into the tools we’re going to develop through this project,” says Michael Cutting. “I hope that in the initial three years, we’ll have a series of decision-support tools with an agricultural focus that we’ll be able to amalgamate with the Climate Change Strategy we’re developing for our region. We’re very conscious to see that these tools provide practical value to the irrigators and farmers who will use them.”

Inspiring conversations

In South Australia’s Marne Saunders catchment, where the project is rolling out a case study on environmental flows, it plans to demonstrate its use beyond direct agriculture: among eco-conscious citizens, some of whom remember a time when the Marne River and Saunders Creek both often emptied into the Murray year round. Dams traversing this vital catchment, together with significant drops in rainfall, have contributed to big declines in the water courses’ health, which water resources manager Tom Mowbray says are speeding up due to climate change.

“There are no easy or simple solutions,” says Tom, who oversees the development of water allocation plans across the MRLB region. “The dams in this catchment are important for people’s livelihoods, for wine growers in the Eden Valley east of the Barossa… We have some pretty good science around these issues, which tell us the likely outcomes of different water policies on streamflows, but it takes a lot of work to convey the science to community members – which is where this project will be so valuable. The tools it’s developing will allow us to play around with different parameters of water use for specific crops versus different temperature ranges, rainfall, streamflows, and other climate parameters, in a really simple, visual way.”

“The key for me is to be able to anticipate how different regions will respond to changing conditions in the future… ‘what will we be able to deal with, and what will I need to prepare for?’ So there’s an optimism in this project – as well as the urgency of the climate change that’s happening before our eyes.”

– Dr Joseph Guillaume, Foresight and Decisions Program Lead, One Basin CRC

Tom believes the models being developed will provide a springboard for important conversations in the community, which will be critical to the next round of revisions of their regional water allocation plans.

“We’re hoping to be able to take these tools to community meetings and say: these are the key problems we’re likely to face, and if we change X or Y parameters these are the likely outcomes. It will simplify some very complex topics and inspire some difficult conversations that we have to have around these issues. There’s not enough water for everything that people want, so where do we make the tough decisions?”

Stuart Sexton, who liaises with communities in the development of water policy, sees the project’s real value being in empowering community members “to take action in what’s likely to be a much drier period”.

“In some parts of the community there’s still a reticence to accept the notion of a changing climate, but if you’re talking about people’s livelihoods that reticence becomes more consequential, so any tool or opportunity that delivers intelligible information to landowners can only do good in promoting more open conversations,” says Stuart. “There are so many people to talk to as well as grape growers and irrigators – grazers, tourism operators, First Nations communities, and anyone who cares for the natural environment and the countless amenities it provides…”

A cultural shift

Joel Bailey, a seasoned hydrologist who runs the Applied Science program at the Murray-Darling Basin Authority, is excited at the project’s potential to provide more “decision-relevant” climate information that’s focused on specific challenges – and therefore is more actionable. “We need approaches to climate risk assessment that start with local issues rather than with climate science,” says Joel, “that start with a challenge in a particular location and work back up towards the science to understand what might play out.

“The MDBA is committed to working with stakeholders as closely as possible,” he says. “We don’t want to be leading off our discussions by discussing ‘emissions pathways’ or ‘time horizons’ – we want to have conversations based on specific risks and adaptation strategies – what will work for you, what won’t, what trade-offs you might need to make.

“Farmers and wetland managers and Landcare groups understand things on the ground so much better than we do, and we need to approach these conversations with humility, because there’s so much we can learn from them. Our agency may collectively have hundreds of years of experience working on and in the basin, but at the local level we’ll never know it as well as these people who live and breathe it every day. So we need a cultural shift, and this project I hope will contribute to just that.”

For Holger Maier, there’s no end to where the new assessment approach can be taken, in terms of understanding the conditions under which people’s values are threatened – and what steps they can take to address those risks. “People are going to have to make decisions in a highly uncertain future,” says Holger. “This uncertainty not only stems from changes in climate, but uncertainties in economic conditions, policy environments, technology developments…

“It is somewhat futile to focus on all the possibilities that the future holds – and not very helpful if we only focus on changes in climate. But by putting people at the centre, the focus moves beyond trying to understand what the future could be like, to understanding the conditions that will prevent people meeting their goals.

“Up to now, climate scientists have been driving this debate – rather than actually asking people what they need. This project is about empowering people to engage according to their situation. ‘What does a rising temperature mean for me, my family, and my community?’ If you’re managing a farm, or a reservoir, or a stretch of river, what particular climate drivers are threatening your work with failure – and what can you do about it now?”

Latest news & events

All news & eventsWebinar recording: Working With Country To Heal

Read MoreBuilding capacity for Basin communities to respond to variable water futures

Read MoreDelivering the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder’s (CEWH) Flow-MER 2025 Annual Forum

Read MoreMurray Darling Association 2025 National Conference: Griffith drives Basin-wide water collaboration

Read More