“Building something powerful”: how One Basin’s first leadership camp and an action-learning program are cementing a platform for lasting change

Written by Ralph Johnstone

It’s not often that a leadership training program takes you back to your childhood. But that was the stirring experience that awaited Dr Tim Weaver, senior lecturer at the University of Sydney’s Narrabri campus, when he travelled 800km due south for One Basin CRC’s inaugural leadership camp deep in the Snowy Mountains.

It was never going to be conventional, but getting together 40 researchers, irrigators, community elders, and government delegates at a retreat near Jindabyne for six days in February proved an exceptionally personal experience – and one that delivered an abundance of unexpected outcomes.

“You tell most academics that you’re going to confine them to a bush-camp for a week, it’s enough to send shivers down their spines,” laughs Tim, who’s the academic lead for the University of Sydney’s partnership with One Basin CRC. “But that’s what we did, and the conversations didn’t stop from dawn till dusk – and into the night as we lay chatting in our bunks.”

There were conversations about wicked problems confronting One Basin’s projects in the basin, about environmental water releases, citizen science, groundwater desalination, and irrigating crops at night. And there were the personal conversations – the ones that rocked Tim’s world – about the kinds of people who make good leaders, and why that is.

“I was talking to one of our First Nations facilitators about two Indigenous sisters who my parents fostered when I was little,” says Tim. “I haven’t been in touch with them for some years – they were much older than me – but when I got home, I rang my Aunty Gloria, my dad’s sister, who’s good friends with one of the sisters, and now we’re back in touch.”

Professional development is always linked inextricably to personal history, according to Liz McCoy, whose company, curious&curious, designed and delivered the Jindabyne retreat, and who over the past nine months has helped One Basin CRC and its partners build a leadership framework to guide its project teams to become better leaders, better suited to tackling the complex challenges they face.

“Making a good leader is not just about role-playing and problem-solving – it’s about personal reflection, being open to other people’s opinions, and being prepared to change your own beliefs,” says Liz. “People who do research generally don’t like taking a lot of risks, whereas innovation and change are all about risk.”

“I’m inspired by the passion and commitment the CRC team exhibits in promoting the health of the Basin. Our waterways are sick and in need, and we have to do everything in our power to care for them…These leaders are our future – they have some of the most important jobs in the country.”

– Liz McCoy, co-founder of curious&curious and One Basin CRC facilitator.

Sharing the journey

One Basin’s Leadership Development Compass identifies a range of different leadership styles and the competencies and attitudes that are central to them. Participants who sign up to the training – more than 30 have already – will be allocated a mentor with whom to share their journey, confide their fears and challenges, and undertake a ‘360° survey’, comprising a self-assessment of their leadership qualities and feedback from colleagues. These assessments will provide the basis for a personal compass, identifying areas in which they might benefit from improvements in their self-leadership qualities (reflection, adaptability, humility), leadership of others (courage, openness, empathy), of impact (strategic thinking, future focus), and of projects (empowerment, collaboration, accountability).

From the competencies highlighted by their compass, the participants and their mentors will develop a ‘personal leadership plan’ focusing on two or three key goals for the coming year. They will meet regularly, using a series of online tools and processes to track their progress on a journey to become their “best selves” – the reflective, empathetic, risk-taking leaders that the basin’s future requires.

One Basin CRC, meanwhile, will develop a cohort of trained mentors and a series of online modules addressing those competencies most often selected by the participants – which will become the core of a program of self-directed learning available to all leaders across the partnership.

“The idea is to help each participant identify which priority they want to pursue – whether it’s building new relationships, empowering their team, improving their communication style,” explains Liz McCoy. “With the nature of their work, most of these leaders have a natural preference for being in the detail and playing small – but the type of leadership many of their projects require is more that of courageous risk-takers who employ masterful language and inspire people to action.”

“When you share your personal stories, you make yourself vulnerable – but you also make yourself more open to change.”

– Tim Weaver, Senior Lecturer in Farming Systems Agronomy, University of Sydney.

Camp camaraderie

The palpable buzz at Jindabyne did not just stem from the participants’ desire to be there, to learn more about themselves or improve their project outcomes. For Teresa Cochrane, a young Dunghutti Gumbaynggirr ecologist studying a PhD in koala preservation at Charles Sturt University’s Gulbali Institute, it was a momentous occasion – one that gave her a new faith in the sincerity of basin leaders to deliver real, equitable change.

“Having these personal conversations with government and industry representatives, realising how closely aligned our goals are, and the fact that these guys really want First Nations leaders to be a part of these conversations – that gave me hope,” says Teresa, who was recently appointed student representative on One Basin’s First Nations Advisory Committee. “It wasn’t tokenistic; there was genuine understanding and engagement, and I think people will hold onto these conversations and think of them next time they’re out on Country.

“The camp was not focused at all on ‘how I view this differently to you’, but on finding common ground, discussing shared goals to conserve water and protect natural ecosystems. When you’re around people for a whole week, the hierarchies are removed, you can ask people what they’ve got out of something, what they really feel about a certain concept.”

“It was great to have the facilitators change up the ways we usually communicate, bringing it back to personal accountability and serious reflection of how we come together as a collective to develop relationships with communities,” says Tim Weaver. “For me, respect and consideration of First Nations perspectives was one of the principal outcomes of this camp. Participants were saying they didn’t realise the depth of connection between Country and the CRC, how much value is being put on First Nations connections and the need to seek First Nations guidance and approval for projects.

“That consultation needs to be there with communities regardless of a project’s orientation; we always need to go to the community where the work is being conducted and discuss its implications. The conversations during the week really underscored for me the sincerity of this group of people to do things right by First Nations communities in the planning of future projects.”

“With natural resources in Australia, it feels more important than ever to have people in the middle who can build bridges between different perspectives. You don’t have to agree with everything other people believe, but you do have to recognise that we share the same values and priorities when it comes to clean water.”

– Teresa Cochrane, First Nations researcher, Gulbali Institute, Charles Sturt University

The power of reflection

Myles Coker, another of the facilitators at the Jindabyne retreat, says good leadership can often start with something as simple as people reflecting on their challenges and concerns. “This was a key theme that emerged from the retreat: the need to create space for reflection – reflection which leads to insight, which leads to renewed energy for change.”

Myles is also facilitating a second arm of One Basin’s leadership program involving an ‘action learning’ pilot to help project teams dig deeper into their leadership challenges and opportunities. Since December, the Incentives and Investments and Stories of One Basin teams have both engaged in a series of meetings to drive deeper leadership discussions about their projects, considering their impacts on a broader range of stakeholders – and ways of engaging more openly and honestly with them.

For the Incentives and Investments team, the time with Myles has seen a new urgency in their mission. In just three months, the team has addressed several challenges in their methodology, fast-tracked a global literature review, and planned a series of co-design activities to engage farmers and communities in investigating new ways of funding sustainable irrigation and ecological work.

“It’s been really useful having a specialist facilitator coming into the team and observing how we interact, and advising us how we can ask better questions of each other,” says Dr Nick Pawsey, Associate Professor at Charles Sturt University and co-leader of the project. “We’d begun to build a strong rapport together, but it’s been great having a facilitator who brings new perspectives and ways of running our meetings… Myles has really helped us refine and validate our research approach, to consider better ways of reaching out and building relationships with different landholders.”

The Incentives and Investments team is looking at novel funding opportunities among investors, banks, and nature repair markets to support farmers and communities to promote sustainability across the basin. “Although these kinds of projects can provide great opportunities for meaningful collaboration, we recognise that there can be different opinions on the current trajectory within green finance and investment markets,” says Nick. “We need to have a lot of honest conversations with farmers and community leaders, as well as with banks, investors, and others who may want to invest in biodiversity markets and basin sustainability.”

A different methodology

“These are conversations that could only take place in the kind of flexible ecosystem created by One Basin CRC, where there’s an openness to explore these kinds of reciprocal arrangements,” adds CSU School of Business lecturer Dr Nicola Thomas, a member of the project team. “I come from a world of briefs and timeframes and budgets, and there’s a totally different leadership methodology here that provides the freedom for us to think outside the box, and progress the kinds of conversations that are so vital to overcoming the toughest challenges facing the basin.”

For Myles Coker, this willingness to broaden the conversation owes just as much to the calibre of the teams and their willingness to engage in reflection and learning. “You have to be vulnerable to talk about leadership challenges, but the groundwork had already been laid in the formative stages of these teams to enable them to engage on a deeper personal and relational level,” says Myles. “High-performance research roles so often focus on data and rules and milestones, but what we’re here for is more about influence and impacts, taking time to think about the ‘butterfly effects’ of your work… The team captured it beautifully when they reflected that it’s not just about the research, but the relationships you build with people along the way.”

“With this group, I’ve been astounded by how well it’s been set up through the One Basin CRC approach to co-design. The level of trust, alignment and understanding between the team members is very high – and on that basis, what can be achieved together will be even stronger.”

– Myles Coker, Director, Innovation & Transformation, GHD.

Since December the team has held four action-learning sessions with Myles, which have seen them unpack what it really takes to engage meaningfully with farmers, irrigators, and Traditional Owners about alternative ways of funding land management projects and sustainable farming practices.

They have also accelerated a wide-ranging literature review of ‘green finance’ frameworks and policies tied to sustainable practices around the world – a task that fell to Dr Valeria Bellan, a behavioural scientist at the Australian Wine Research Institute. “There were 150 papers to review and analyse in detail, which was a huge task,” says Valeria. “But the commitment and support of the team enabled us to identify a post-doc researcher who I’ve now been able to share this work with.”

Like those who attended the Jindabyne event, Valeria says One Basin’s focus on creating cohesive teams has given its members the confidence to share any concerns that may arise in the course of their work. “Before this project got underway, the CRC and our team leaders arranged for us to meet in Loxton, which really set the scene for the progress we’ve made so far. Those long car journeys enabled us to connect, and having dinner together – it was really lovely. Meeting one on one is so important; we’re social creatures and that connection really changes everything.”

“A total contrast”

For Nicola Thomas, that sense of camaraderie and trust among a team who really respect each other can deliver positive outcomes – no matter how high the environmental, financial, or historical hurdles.

“I’ve done leadership training with consultants zooming in from different places, or brought together for a day – but they never really get to know each other,” says Nicola. “This is a total contrast. The investment by One Basin CRC in getting us together before the project, and again at the annual event, is really paying off.

“There’s a real commitment within this team; everyone’s really invested in it. Even designing a flyer for our first workshop – everyone had an opinion and wanted to contribute something, because everyone really wants it to succeed.”

For Myles Coker, like Tim Weaver, the Jindabyne event felt like an emotional turning point for many of the projects involved. “I think that week was deeply meaningful for a lot of people,” says Myles. “Something deep seemed to shift… I think there’s great potential for change in many of these relationships.

“There was already a strong platform for change, and I believe we can build something powerful on that. It’s very bold, to get a group of scientists and technical people to reflect on how they work together – it’s a massive departure from the status quo.”

“The One Basin CRC has enabled us to establish a strong interdisciplinary team and partnerships across industry and research organisations. The training has been influential in helping us strengthen these bonds.

I think it would be useful for every new team to have a chance to have these kinds of intimate meetings and the open, honest chats they engender.”

– Dr Nick Pawsey, co-lead, One Basin CRC Incentives and Investments project.

More information on some of the methodologies that are informing the basis for One Basin’s leadership development program:

Helping Basin communities thrive

Written by Katherine Seddon

Across the Murray-Darling Basin, communities are exploring practical ways to address water scarcity challenges. Community Wealth-Building programs are emerging as one promising framework that may help rural communities adapt to limited water availability while maintaining economic resilience.

Changing rural economies

Decreasing water availability in the Murray-Darling Basin is threatening traditional economic models and communities are seeking alternative economic approaches.

Research by Miltone Kimori, a doctoral researcher with One Basin CRC at Charles Sturt University’s Gulbali Institute, suggests that Community Wealth-Building programs offer a practical approach to regional development that focuses on using existing community assets rather than relying primarily on external investment.

Working through the One Basin CRC’s Griffith hub, Kimori’s research examines how Community Wealth-Building programs might best be designed to help Basin communities adapt to reduced water availability. His work investigates the relationships between these programs and various community resources—including natural assets, cultural heritage, social connections, and governance structures.

“Community Wealth-Building represents a paradigm shift, “Kimori explains. “It is about recognising and leveraging the multiple forms of capital within a community – naturally, cultural, social and economic – to create sustainable solutions.”

Anchor institutions leading change

At the forefront of this movement are anchor institutions like the Western Murray Land Improvement Group (WMLIG), organisations deeply rooted in local communities that use their resources to stimulate economic development.

The WMLIG’s initiatives, such as the Murray Industrial Hemp project, demonstrate practical applications of Community Wealth-Building principles by investigating alternative crops like hemp that may use less water while also providing new market options for local producers. According to Kimori’s research framework, effective Community Wealth-Building approaches consider multiple forms of community capital working together.

“What makes these programs successful is their holistic approach,” Kimori says. “They recognise that community wellbeing depends not just on financial capital, but on natural, cultural, social, and built capital working together in harmony.”

“Organisations like Western Murray Land Improvement Group represent crucial anchor institutions in the Murray-Darling Basin’s adaptation journey,” explains Miltone Kimori.

Kimori’s research examines how not-for-profit organisations serve as catalysts for sustainable economic development in water-constrained environments. By documenting WMLIG’s methodologies in facilitating local investment, promoting climate-adaptive agricultural practices, and strengthening community capacity, his work aims to develop an evidence-based framework that can be used by other organisations throughout the Basin.

“What makes Western Murray Land Improvement Group interesting is their integrated approach to community resilience,” Kimori says. “They’re simultaneously addressing ecological sustainability, economic diversification, and community empowerment— which is exactly the multi-dimensional strategy that effective Community Wealth-Building requires.”

The research uses participatory methodologies to document how WMLIG’s initiatives create feedback loops that have local benefits. This is where economic activity generates social and environmental returns that remain within the community rather than flowing outward. This practical application of Community Wealth-Building principles can be used as an example for other Basin communities seeking sustainable development pathways.

Collaborative knowledge networks

Complementing these on-ground initiatives is the work of Associate Professor Tahmid Nayeem, who leads the “Unlocking collaborations for transformation” project for One Basin CRC. This project aims to improve climate adaptation strategies by mapping stakeholder networks and developing platforms for knowledge sharing.

“The challenges facing the Basin cannot be addressed in isolation,” says Dr Nayeem. “An effective adaptation requires collaborative ecosystems that inform better decision-making no doubt.”

This collaborative approach aligns perfectly with Community Wealth-Building principles, which emphasise participation and collective ownership of resources. By involving communities at the design phase, these projects ensure that economic development strategies actually reflect what the local community values and needs.

Social marketing for community engagement

A critical component of successful Community Wealth-Building programs is effective communication and community engagement. Kimori’s research also explores how social marketing strategies can improve program uptake by aligning with local values.

“For these initiatives to succeed, communities need to understand not just what Community Wealth-Building is, but how it benefits them specifically,” Kimori explains. “We’re using participatory action research to develop communication approaches that speak directly to local concerns and aspirations.”

This focus on participatory methods ensures that community voices remain central to the research process. Through workshops, interviews, and collaborative design sessions, researchers and community members co-create solutions tailored to the unique challenges of Basin communities.

Building future resilience

As climate variability affects water availability in the Basin, community-centred approaches like Community Wealth-Building may become increasingly relevant. The One Basin CRC’s Griffith hub serves as a connection point for this work, bringing together researchers, community organisations, and stakeholders to explore sustainable options.

“What we’re ultimately working toward is a future where Basin communities don’t just survive water scarcity but thrive despite it,” says Kimori. “By building on local strengths and fostering collaborative networks, Community Wealth-Building programs offer a promising framework for that future.”

These research projects and community initiatives provide insights not only for the Murray-Darling Basin but potentially for other rural communities facing similar environmental and economic transitions.

First Nations leadership supporting Savanna Science in South Africa

Written by Caleb Back

The 22nd Savanna Science Network Meeting (SSNM) in Kruger National Park became an unexpected forum for a critical dialogue: the transformative role of First Nations knowledge in water science and governance. That’s according to First Nations Program Lead Professor Troy Meston and First Nations Engagement Lead Geoff Reid, who represented the One Basin CRC at the conference and underscored this theme. Sparking conversations about First Nations leadership in environmental management, they presented a perspective often overlooked in global scientific discourse.

At the conference, Meston and Reid’s presentations stood out for their emphasis on integrating First Nations knowledge with Western science in the Murray–Darling Basin. Their talks began with an Acknowledgement of Country, a practice unfamiliar to many South African attendees.

“This wasn’t just protocol it was a statement that First Nations stewardship is inseparable from sustainable water management,” Geoff Reid said.

“It was our first opportunity to raise awareness to international audiences the Cultural practices and traditions of First Nations people,” Mr Reid said.

“Highlighting this relationship of First Nations stewardship and caring for Country helped set the scene for the international conference on understanding how we view water in the Basin,” he said.

“First Nations people understand the ‘language’ of rivers—the signs of health, the rhythms of drought and flood.”

“Science alone isn’t enough,” Geoff Reid said.

The CRC’s work highlights a growing recognition: First Nations communities, with millennia of ecological knowledge, offer unique insights into biodiversity, seasonal flows, and drought resilience. In the Murray-Darling Basin, where over 40 First Nations communities hold deep cultural connections to waterways, their exclusion from decision-making has historically led to mismanagement.

Part of the CRC’s mission seeks to rectify this by embedding First Nations leadership in its research—a model that resonated with South African scientists grappling with similar post-colonial challenges.

A striking contrast emerged during the meeting: while Australia struggles to include First Nations in water governance, South Africa has shifted to state-controlled water management post-apartheid, with Black African leaders now steering policy.

“South Africa’s transition shows what’s possible when marginalized communities reclaim agency,” Professor Troy Meston said.

This disparity inspired a proposed collaborative project between the CRC and South African institutions like the University of Mpumalanga (UMP).

“The initiative would study South Africa’s governance reforms to identify pathways for First Nations-led water management in Australia,” Professor Meston said.

“This helped frame questions for us to investigate, looking back on our own history of Basin management,” he said.

“How did South Africa build capacity for leadership? What policy frameworks enabled equitable participation?”

“Answering these questions could help inform Australia’s approach, particularly in training First Nations water scientists—a field where Australia lags behind South Africa,” Professor Troy Meston said.

The launch of Charles Sturt University’s Sustainable African Rivers Initiative (SARI) program during the conference further highlighted synergies. SARI, which focuses on freshwater conservation in Africa benefits from South Africa’s advanced environmental flow monitoring techniques.

“A joint study comparing the Limpopo and Murray-Darling Basins could yield cross-continental innovations, such as adapting Australia’s water allocation models to African contexts—and vice versa,” Professor Meston said.

“Building on existing relationships within the CRC, such as with Charles Sturt University, highlight the strengths of our model – that even in South Africa we still have opportunities to collaborate with each other,” he said.

Beyond the conference, Meston and Reid’s visit to Soweto underscored the parallels between First Nations and South African experiences. The township’s history of apartheid-era displacement and resistance echoed the struggles of First Nations communities. Both groups face legacies of land dispossession and water inequity—yet both have harnessed cultural resilience to advocate for change.

At the Hector Pieterson Memorial, Reid reflected on these shared histories.

“The youth-led Soweto Uprising was a fight for dignity, much like First Nations’ battles for water rights,” Geoff Reid said.

“Science must honour these stories by centring Indigenous voices,” Mr Reid said.

“Understanding the history of dispossession from Country is important as we continue to work with First Nations communities, acknowledging the challenges and wrongdoing that has been inflicted on communities,” he said.

“This history continues to reverberate and is central to working not just towards reconciliation, but including First Nations voices in the solutions for improving resilience in the Basin.”

The CRC’s South Africa trip revealed that global water sustainability depends on First Nations leadership. Proposed projects with South African institutions aim to formalize this ethos, from co-badged PhD programs to governance research.

“The Murray-Darling Basin won’t heal without First Nations at the table. South Africa’s journey proves it’s not just possible—it’s essential,” Professor Troy Meston said.

“The conversations held throughout South Africa highlight the opportunities available to the CRC to build relationships, advance world-class science, and drive First Nations leadership in the water space – not just within the Basin, but internationally as well,” he said.

For policymakers and scientists, the message is clear: The future of water science isn’t just about data—it’s about justice, collaboration, and the wisdom of those who’ve lived with these landscapes for generations.

Water-saving techniques reducing costs for Northern Basin growers

Written by Caleb Back

Cotton is a thirsty crop, but what if we can reduce its overall water consumption? That’s what Goondiwindi Regional Hub Manager Marti Beeston travelled to Dirranbandi to find out.

Joining Cotton Australia, the peak body for Australia’s cotton growers, Ms Beeston visited ‘Clyde’, one of Australia’s largest cotton growing properties run by 2024 Grower of the Year award recipient Scott Balsillie.

Based south of Dirranbandi Ms Beeston toured the property to learn how innovative approaches to irrigation have led to significant improvements in the crop’s consumption of water across the property. Or simply put – owners have learnt how to use water more efficiently.

“Clyde is a fascinating example of how farmers are always looking to get more out of their water and improve yields. The work that Scott has put into his property is a testament to the ingenuity of irrigators,” Ms Beeston said.

“Scott has worked hard to develop and diversify his property through improving monitoring and implementing more efficient ways to irrigate.”

“The biggest improvement he showed us were the bankless channels which are an innovative alternative to the industry standard of siphons,” she said. “Bankless channels use gravity to feed water deeper into the crop. Scott started by grading the paddock at a slight angle, with a head ditch at the top and a tail drain at the bottom.”

“Bankless channels were shown to have saved 2.5 megalitres a hectare, going from 10 megalitres per hectare down to 7.5 megalitres.”

On large properties like Clyde, and with such a thirsty crop as cotton, that’s a big saving.

“Water fills in the head ditch and slowly filters down into the bottom of the crop, as the channels are cut much deeper than traditionally seen with siphons – allowing for the water to really get where it needs and avoid runoff,” Ms Beeston continued. “Excess water then flows down the paddock and into the tail drain, where it’s transported to another paddock for use.”

“This means Scott not only gets more water to where it needs to be and improve yields, but also save water, reduce evaporation, and save in machinery and labour costs,” Ms Beeston says.

The visit to Clyde also provided an opportunity to connect with the community, stakeholders, and irrigators in the region.

“As a hub manager, part of my role is to keep our partners informed about One Basin CRC’s research projects and showcase opportunities to improve on-farm practices such as efficient water use. Coming to Clyde is a great way to engage with irrigators in the region, as we seek to develop industry-led solutions that support Australia’s irrigation regions to be the most productive, resilient, and sustainable in the world,” Ms Beeston said.

“Goondiwindi is home to a large cotton growing community, particularly out west of the town towards St George and Dirranbandi, where Clyde is located,” she continued.

“There’s a lot of innovation happening in the region. Soon we’ll be unveiling the upcoming evaporative losses project, which will find new ways to save water in the cotton industry by reducing water loss from irrigation dams.”

“This project will be based in the Goondiwindi-St George Area and will benefit properties like Scott’s and many others.”

The evaporative losses project will be a place-based research project in collaboration with the University of Southern Queensland and the Queensland Department of Environment, Science, Tourism, and Innovation. A PhD and a postdoctoral student will be funded as part of the research, to be based at the Goondiwindi Regional Hub.

“To ensure our research projects respond to the current and future needs of industry, users, and communities, we’ve made the commitment to undertaking place-based, industry-led research. This collaborative approach not only supports our regions, but means project outputs are guided by the users who will hopefully adopt them,” Ms Beeston says.

“With the formal commencement of the project just around the corner, we’re looking forward to working with irrigators in the northern Murray–Darling Basin and find new approaches to water use in a region constantly at threat of climate extremes,” she said.

“If you’re an irrigator in the northern basin with significant dam storage, reach out to the Goondiwindi Hub and get involved.”

Learn more about the Goondiwindi Regional Hub.

To stay up to date with the evaporative losses project, subscribe to our newsletter here.

Loxton RAC appoints new Chair

Written by Caleb Back

Tim Smythe has joined the Loxton Regional Advisory Committee (RAC) as the new Chair, overseeing a committee responsible for exploring community outcomes within One Basin CRC projects to maximise impact and support place-based research.

Tim is an easy choice, with an impressive background across not just state and local governments, but also having experience in technical viticulture management, wine industry development, and a well-respected regional presence.

His extensive resume includes Chief Executive of the Murraylands & Riverland Local Government Association, Regional Coordinator with Primary Industries & Regions SA (PIRSA), Mallee Sustainable Farming, and in the Riverland Wine Industry Development Council.

A problem-solver who builds relationships and focuses on end-to-end systems approaches, Tim brings with him an analytical approach that will support projects to identify new steps and learning opportunities.

Tim stood out as a highlight for his keen focus on partners’ needs for practical outcomes and his extensive community knowledge. We wish Tim the best in his new role and look forward to watching the Loxton Regional Hub continue to grow.

Learn more about the Loxton Regional Hub.

New Loxton RAC Member

The Loxton region has welcomed its newest member to the Regional Advisory Committee (RAC) – Amy Goodman.

A Water Manager at the Central Irrigation Trust (CIT), Amy is responsible for the Water, Land and Customer Services, which supports members’ water rights, policy, compliance, and water trading functions and liaison.

Like many RAC members, Amy is a tried-and-true member of the community, originally growing up on the family farm in the Riverland of South Australia where she developed a keen interest in water management.

She kicked off a 20-year career working with government, industry, and not-for-profit organisations on community-led natural resource management programs.

In addition to her local experience, Amy holds a Bachelor of Applied Science (Agriculture) from the University of Adelaide and is a Graduate of the Leaders Institute of South Australia’s Governor’s Leadership Foundation Program.

First Nations Data Sovereignty co-design at ANU

Written by Caleb Back

The One Basin CRC’s First Nations Research Program has taken a significant step forward, with First Nations Program Leader, Professor Troy Meston, delivering the program’s first co-design meeting with the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra.

This session focused on First Nations Data Sovereignty, the first of many First Nations-led projects identified in the CRC. The issue is critical, as communities across the Basin call for control over their own data, historically collected and used without Cultural approval. According to Professor Troy Meston, this has led to deep-seated scepticism toward institutions and a pressing need to rethink research engagement.

“Data sovereignty is a major barrier for First Nations-led research, so it makes sense for the CRC to tackle this challenge first,” Professor Troy Meston said.

“Communities need access to historical and contemporary information to build organisations, conduct research, repair Country, and protect Cultural knowledge,” Professor Meston said.

“Repatriating data according to Cultural needs allows us to reset the clock,” he said.

Dr Hannah Feldman, researcher in the School of Cybernetics at ANU, convened experts from diverse fields, including Indigenous technology and data scientists, ecology, cybernetics, and Indigenous water management. The session explored the complexities of First Nations data sovereignty and steps toward repatriating data to communities.

Hannah’s involvement stems from her commitment to ethical research and collaborative knowledge-sharing, as well as the possibilities for cybernetics – using a full systems approach to exploring complex technological challenges – to support data sovereignty.

First Nations data encompasses all data collected relating to People and Country, including oral histories, geographical mapping, environmental knowledge, and community records, existing in both physical and digital formats. Differing from Western data frameworks, it requires culturally appropriate protocols for storage and access that reshape how data is handled.

“Data repatriation won’t be an easy task. Communities will face barriers including legal restrictions, intellectual property laws, institutional bureaucracy, and once again paving new ways forward in the era of rapid tech and data development” Dr Hannah Feldman said.

“We have an opportunity through cybernetics and the CRC partnership to support all aspects of what that might look like, from technical requirements, right through to governance, community, and Country impacts,” Dr Feldman said.

“Addressing these issues requires a shake up in the way Western systems manage, store, and think about data,” she said.

Data repatriation is more than handing over information; it involves ensuring communities can access, grow, and manage their knowledge, as well as ensuring that the communities “handing over” any data are also appropriately supported to do so in useful, impactful, and ongoing ways.

Research efforts focus on developing secure digital repositories, Indigenous-led governance models, and ethical data-sharing principles will be critical for all organisations and communities in this complex data ecosystem to work together and continue water justice efforts through data.

“This project will be wholly First Nations-led, ensuring data is securely repatriated for community benefit,” Professor Troy Meston said.

“The digital divide is a critical issue – without access to tools and infrastructure, communities cannot fully control their information,” Professor Meston said.

Improving digital literacy is key to ensuring communities can access and control their data. Future project pathways will focus on governance structures, education and institutional investment in long-term infrastructure.

For many First Nations communities, reclaiming control over data means rethinking relationships with governments, universities, and institutions. Establishing governance structures that reflect First Nations decision-making is crucial, but requires shifts in institutional operations.

“There isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach; each community and organisation will have a range of strengths, challenges, and supports,” Dr Hannah Feldman said.

“The data we’re talking about takes a number of forms, including audio files, maps, video, and many more” Dr Feldman said.

“Supporting how institutions and communities engage with these forms of data is a complex and exciting opportunity, and an opportunity that needs to have far more contributing voices than just government, academia, or communities themselves,” she said.

“I’m really excited to shake up conversations on First Nations data sovereignty and play a role in ensuring its repatriation to communities.”

First Nations data sovereignty requires a collaborative and holistic approach. Co-design is just one step toward broader societal change. By engaging with like-minded institutions, better ways of storing, disseminating, and sharing information can be developed, strengthening the relationship between First Nations communities and their Cultural knowledge.

This first meeting has helped the One Basin CRC to consider its thinking and bring a multidisciplinary approach to this project’s design. What does good governance of centrally held data look like? Is it centrally held? Can it generate revenue for a First Nations led Data Sovereignty organisation? If successful, can this be a model for other countries? If AI is introduced, can it become a dynamic resource to house knowledge beyond what we think of as historical libraries? The One Basin CRC looks forward to continuing to share the story of this research journey.

Learn more about the First Nations research program.

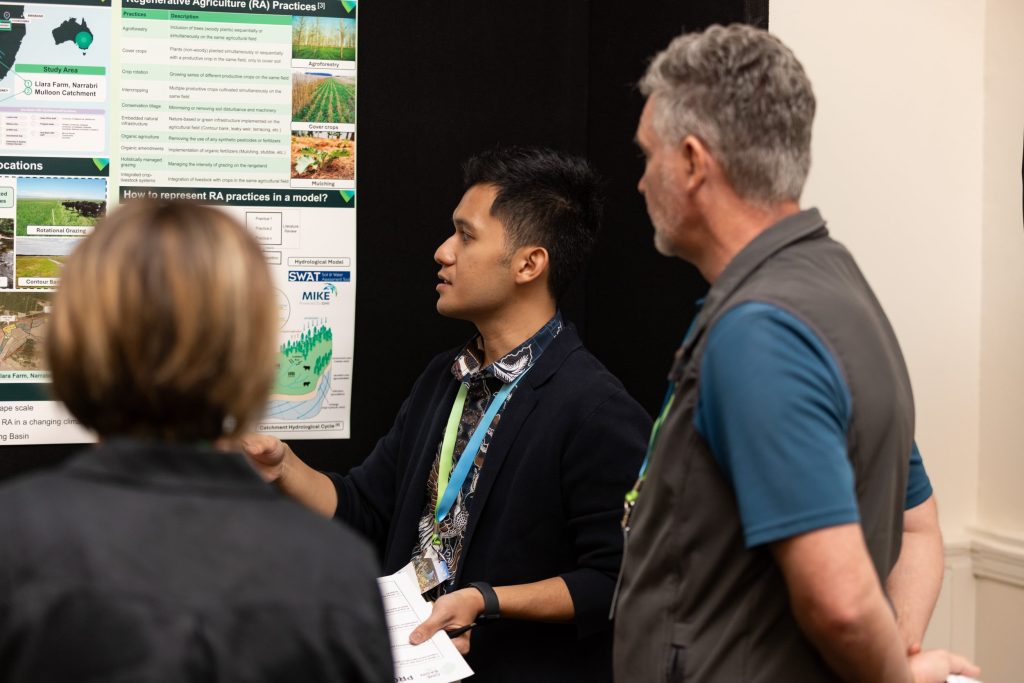

A regional ‘dream team’: the PhD scholars who are bringing world-class research to the banks of the Murray-Darling Basin

Written by Ralph Johnstone

There’s a lot of lateral thinking going on at the One Basin CRC hub in Mildura these days. Crop scientists, drought monitors, and renewable energy researchers come and go, but there’s a growing group of PhD students – many of them now stationed here permanently – who are breaching once-insurmountable barriers as they take on some of the toughest challenges facing Australia’s largest river catchment.

Camaria Holder and Kelsy Burns, two doctoral candidates from Antigua and Australia, are preparing to help community groups raise their voices in discussions on long-term climate adaptation: Camaria upriver in the vulnerable Goulburn-Broken catchment; Kelsy up the road, at a little lake that’s losing its battle with rising salinity. Shahin Solgi, a charming Iranian scholar, is visiting from Loxton, where his modelling of long-term irrigation demands for different grape varieties holds significant interest for cultivators of the Riverland’s largest crop.

Next door, Tristan Graham, the CRC’s first post-doctoral researcher, is also focused upstream, on the Barmah-Millewa Forest near Echuca, where he’s developing an evaluation tool with river and environmental managers to better understand and inform their decisions on water transfers.

And in February, the team were joined by Lang Zheng, a modest young data scientist from Hong Kong, who believes the predictive power of AI can help Australian irrigators find a more efficient balance between specific crop needs, evaporation rates, renewable energy sources, and variable pump operations.

If One Basin’s first tranche of PhD students appears on paper to be something of a dream team, it’s testament to the tight-knit partnership between the CRC, its six affiliate universities, and a growing number of government and industry partners who share the view that pioneering scholars are critical to the future of this vital river system.

The other part of One Basin’s PhD program that’s reaping dividends is its stipulation that candidates spend most of their three-and-a-half years of study in one of its regional hubs – Griffith and Goondiwindi alongside Loxton and Mildura – where they can directly experience the needs for their research, and rub shoulders with the industries that could benefit from it. Ideally, when their goals align, the CRC is encouraging its partners to sign up students for a part-time internship to address a “real world challenge” facing their operations.

“If you’ve identified a thorny issue that needs resolving, and we have a student with expertise in that field, it makes great sense to have that student embedded in your organisation,” says Wendy Craik, Chair of the CRC Board and a keen advocate of the PhD program. “Some companies may fear they’ll be lumbered with an employee, but if you have someone in your firm who’s becoming an expert in their field, they’ll have an eye for these things, they can see things that need to be changed or done in a more effective way – and they’ll be a lot less expensive than a consultant.”

| Current no. of PhD students with scholarships | 16 |

| Projected no. of PhD students by 2027 | 30 |

| Current or confirmed internships | 5 |

| No. of partnering universities | 6 |

| PhD program by gender | 6 F / 10 M |

| PhD program by nationality | 4 AUS / 12 Int. |

State-of-the-art research

In January, the CRC welcomed its first formal internship when Wiyanda Aflah, a hydrological modeller from Indonesia, joined the Melbourne office of environmental engineering company Water Technology to undertake a literature review of water storage on farmland and floodplains.

Brian Jackson, Water Technology’s group lead for digital solutions, says Wiyanda is already contributing “important research and state-of-the-art understanding” to the company.

“He’s very switched on and is deeply engaged in this foundational work to investigate how remote sensing by satellites can help us model water extents beneath riparian and floodplain tree canopies,” says Brian. “This partnership with One Basin and the University of Sydney is keeping us at the forefront of research in this area – which promises significant potential for environmental flow management and productive water for agronomy.”

In June, Lang will commence the first phase of an internship with SA Water to study their pumping operation practices, and after submitting his thesis, he’ll rejoin the state water provider with a potential opportunity to trial the developed techniques on their systems. Camaria and Kelsy, meanwhile, are negotiating internships related to the Water Futures research project. Kelsy has also secured a part-time job as an extension officer with the Pistachio Growers Association, while Shahin spends a day each week supporting researchers from the South Australian research institute, SARDI – both jobs with clear links to their fields of study.

One Basin’s education and training manager, Dan Pierce, says it’s clear the natural synergies within the CRC ecosystem are beginning to bear fruit among the current crop of PhD students. “Several students are already contributing to CRC research projects and a number of government and industry partners have agreed to host internships and placements,” he says. “This shows great promise for our partnerships, as a growing number of organisations see the rich potential for students to continue their research within the industries – and the regions – that can put it to best use.”

Some industry partners are also beginning to play a role in developing PhD projects to support their work. From April, Adelaide-based innovator Osmoflo will start co-funding a doctoral student in Loxton to study opportunities to replicate the groundwater desalination technology they’ve been trialling at nearby Century Orchards. “This represents a natural progression from a CRC project that’s brought together the brilliant hydrological modellers at the University of Adelaide with a progressive tech company and a farsighted grower to address uncertainties in river water availability,” says Dan Pierce. “A PhD researcher will be the catalyst for taking the partnership further and looking at the potential to use the technology elsewhere in the basin and beyond.”

“Once there are enough scholars based in the regions – and hopefully staying and getting jobs after their PhDs – hopefully we can build a critical mass and find a way to sustain it in the long term,” adds Wendy Craik. “If we can inspire this, I believe the CRC and the community and local industry will all benefit, and the researchers will get a clear steer from industry about what the main issues are – so they become more trusted than your average student or consultant flying in from Melbourne or Sydney.”

“The PhD students are not cloistered in a university, removed from their area of study – they’re right in the heart of it, co-designing with the communities who are living the challenges they’re addressing every day.”

– Jane O’Dywer, CEO, Cooperative Research Australia

Better remuneration, and job prospects

Although the number of annual PhD completions in Australia has more than doubled to exceed 10,000 in recent times, doing a PhD here continues to face many hurdles – as rising living costs outweigh stipends, and a growing number of students elect to go straight into full-time work. One Basin CRC is proactively trying to bring down these hurdles, offering a generous annual stipend of up to $51,300, which with additional operational funding and potential part-time work, provides a comparatively generous package.

Then there’s the clear employment potential of a One Basin PhD, with research topics increasingly aligned with the ecological work and sophisticated technology of public and private companies – rather than the labs and universities that are the traditional milieu of PhD graduates.

Among the many heartening developments over the past year has been a deepening partnership between One Basin CRC and the Murray Darling Basin Authority (MDBA), which as the government agency responsible for coordinating water resource management across the basin, is a critical Tier 1 partner in some of the CRC’s most prominent and ambitious research projects.

Andrew Kremor, head of the integrated river modelling uplift program at MDBA, says the agency has “great faith” in One Basin’s ability to identify suitable PhD students to join the MDBA as interns supporting the four projects it’s currently involved with.

“We’ve made an in-principle commitment to provide five PhD students with six-month internships, working closely with our scientific teams,” says Andrew. “We think this is a fantastic opportunity through which the CRC will provide its students with valuable on-the-job experience, the candidates will enhance their growth and career journeys, and the MDBA will get high-quality students to work on aspects relevant to the agency. Plus some of them may find ongoing employment within the MDBA – which we see as a logical extension of these internships.”

Andrew’s team has been facing up to a national shortage of high-quality hydrological modellers, and he’s currently working with One Basin’s research director Seth Westra to potentially develop a workforce development program, which could broaden the partnership’s capacity-building to other in-demand disciplines – such as water engineering, social science, First Nations research, and agricultural economics.

“Hydrological modelling is facing a huge shortfall,” says Andrew, “and we want to get ahead of the trend and develop a program supporting all four states to attract more talent, train them up, and send them out to industry – and internships and PhDs are an important component of that.”

While relationships with the MDBA and Research & Development Corporations (RDCs) are critical for One Basin to build its skills development capabilities, Seth Westra says an equal challenge is in supporting smaller businesses and community groups to build their own research capabilities.

“At the moment in agriculture most research happens in RDCs or government agencies that employ PhD students, but if you go to community groups or smaller farming businesses, the value of research is often more challenging to communicate and integrate into their business models,” explains Seth. “We recognise the priority placed by our industry partners on building the sector’s capacity for innovation, and our universities are keen to meet this demand – so One Basin CRC really has a critical role to play as a catalyst in this process.”

“Students who base themselves in the regions are giving themselves a serious advantage when it comes to applying for in-demand jobs.”

– Leonie Burrows, Chair, Strategic Advisory Panel, Mallee Regional Innovation Centre

Talking farmers’ language

Talk to many people in the CRC’s blossoming alliance – now numbering 88 partners – and you begin to hear the same advice over and again. About persuading private companies of the importance of research. Talking farmers’ language. Making the impacts of research tangible, and directly relevant to the struggles they face every day.

“The CRC’s PhDs are part of a very exciting program,” says Peter O’Donnell, CEO of Southern Cross Farms and a member of the CRC’s Mildura Regional Advisory Committee. “I don’t think the local community realises the intellectual powerhouse it has working for it.

“But we need to make more efforts to message farmers in language they can understand – tell them ‘you’re going to get more fruit for the same amount of water’. There’s a language for farmers, for industry and tourism – and it’s not the language of academia.”

Leonie Burrows OAM, who chairs the Mildura RAC and MRIC’s Strategic Advisory Panel, and has a lifetime of leadership roles in local government and regional development, agrees. “We have a lot of academics in Australia who are brilliant scientists but often lack the skills to communicate with growers and farmers,” she says. “If you want to talk to people on the land, host a barbecue, talk straight, and focus on outcomes – without couching everything in scientific language. The Mildura hub manager is really across this, helping students connect with industry people on the ground, and MRIC is helping with these connections.

“I hope some of these students will stay, be sponsored by water and environmental businesses, or horticultural peak bodies, so that after the CRC winds up our communities will have a pool of researchers who are based in the regions and keep contributing. These are really great people to have in our community.

“We’re crying out for extra skills in horticulture and water – there are amazing roles available here in engineering, agtech, irrigation management, agronomy, and social science. Students who base themselves in the regions are giving themselves a serious advantage when it comes to applying for these jobs.”

“These students are all great human beings with a lot of experience, and their hearts are in the right places. What they have to contribute to the Murray–Darling Basin is significant both in terms of their research and their commitment to finding solutions that will save water and crops in a climate-afflicted future.”

– Peter Forbes, Mildura Regional Hub Manager, One Basin CRC

A growing family

With five of its first tranche of PhD students based in the regions, a ‘second wave’ is now on the way: one arriving in Griffith at the end of March, and a further two likely to land in Loxton by the end of April. The managers of the four hubs are celebrating these small wins like proud parents – and the comparison is not as far-fetched as it sounds.

PhD students coming to a region usually know no one in the town (in some cases, anywhere in Australia), so their reliance on the hub managers is critical. The CRC has been careful to nurture a team of personable and empathetic managers, who don’t mind working out of hours to help their charges – initially finding them somewhere to live, or buying a car, or paying bills, but also taking them to social events, introducing them to ‘like minds’.

For many of the students, the hub managers become – if not parental – at least trusted friends, helping them find their feet in a new place, and a new culture. When Shahin Solgi arrived in Loxton, hub manager Kym Walton became his touchstone, his sons taking Shahin to the pub and the footy, introducing him to their mates. “Kym is such a special guy,” says Shahin. “I couldn’t have done any of this without him.”

In Mildura, the students are more fortunate, having the ever-attentive manager Peter Forbes, as well as sharing their premises with the Mallee Regional Innovation Centre (MRIC), whose CEO Rebecca Wells and her team have also been a huge support helping them find homes, connect with the local SuniTAFE, and – critically – meet a steady stream of researchers and their Strategic Advisory Panel, which plumbs a rich well of water and horticultural knowledge.

Then there’s the intra-university collaboration between La Trobe and the University of Melbourne, which has made sure all the students have “a proper office setup”, with decent desktops, standing desks, a meeting room for video calls, and loans from the SuniTAFE library. “These are erudite researchers doing vital research,” says Rebecca. “They need the right environment.”

Location, location, location

Being embedded in the right environment makes all the difference, according to Seth Westra. “We understand that doctoral students need to work closely with their academic supervisors,” he says, “but it’s equally important that they’re living and breathing the world of their sponsoring industry – and connecting their research directly to the needs of the local communities. That’s why it’s so important for us that they’re based in the hubs.”

“If you’re based in a region, the relationships you can build with industry stakeholders are more authentic, and regional people respond well to people who care about the issues they care about,” adds Kym Walton. “It’s much more meaningful than a fly-in, fly-out service. Having a deeper understanding about how an industry operates, how particular crops are grown, a real understanding of how things work – that’s fundamental to developing a needs-based solution and building trust between researchers and industry.”

While some universities have higher expectations of PhD students being on campus, some – CSU is an oft-quoted example – are more adept at guiding students remotely. But the CRC’s PhD program seems to be making strides in winning over supervisors across the basin.

Professor Andrew Hall, Shahin Solgi’s supervisor at CSU’s Gulbali Institute and himself a CRC graduate, says he’s delighted with his student’s progress: “The success rate for CRC PhD students is very good, partly because of that extra layer of support. I am confident this will also be the case for the One Basin CRC: support from excellent hub managers, plus the research training the CRC provides on top of the supervisors’ academic support.”

Wiyanda’s supervisor at the University of Sydney, Professor Willem Vervoort, says that while it can be challenging for supervisors to see enough of their students when they’re based in the regions, One Basin’s focus on industry relationships augurs well for its graduates.

“Wiyanda is definitely looking at opportunities to stay in Australia,” says Willem. “Given the investment from the CRC, it’s important to keep these young scientists in our country. But there’s also an opportunity here to provide great leadership in Indonesia – which I believe is a valuable investment for Australia’s future as well.”

“I don’t think the community realises the intellectual powerhouse it has working for it.”

– Peter O’Donnell, CEO, Southern Cross Farms

It is this faith in the future – in a future in Australia – that provides lasting hope from a conversation with these bright and dedicated young researchers.

“My preference would be to stay and join a water utility after graduation, which aligns with my choice of an industry-oriented PhD program,” says Lang. “It feels like home from home here,” says Camaria. “Going to watch Kelsy playing footy, going to the market, the Deepavali festival, the great community at church… there’s enough here to keep me going!”

Perhaps the last word should be reserved for Shahin, who charmed the participants at last year’s One Basin annual meeting with his honest reflections of life as “Loxton’s only Persian”.

“Yes, it’s been challenging,” he says with his trademark honesty. “Many people here are all about footy and cricket and Aussie TV – and I’m not familiar with any of it! But there’s a good reason I’m still here. I’m learning so much… and I know that I’m going to be solving real-world problems – rather than just sitting at a desk for three-and-a-half years and doing literature research in a library.”

Webinar recording: Irrigation suppliers and service

A key cog in the wheel of on-farm production.

As the suppliers/retails/service techs are key to water delivery to irrigation properties, how do we train, attract and retain staff in areas with dwindling populations. How do we ensure consistent supply of parts and machinery when the majority is imported.

Does this sector of the agriculture market receive enough attention and support? What is needed to further support on-farm adoption of water saving technologies?

Listen to our expert panel to hear their perspectives on these important questions:

- David Cameron, CEO of Irrigation Australia

- Nick Higginbottom, Emmetts Irrigation

- Kelli McDougall, AgriTalent

- Avril Hogan, COO, One Basin CRC

Organic waste conversion win-win for Basin communities

Repurposing organic matter to improve soil fertility could be a game-changer for rural communities, measured and confirmed via an extensive community-led project funded by the One Basin CRC. That’s according to the Project Lead Roger Knight, Executive Officer of the Western Murray Land Improvement Group.

Repurposing agricultural waste, timber byproducts, and other organic matter could be repurposed into a high-quality fertiliser, called biochar, to improve soil health, soil carbon and water retention.

“Biochar is a product similar to charcoal and is produced by heating organic matter in a controlled process with limited oxygen, called pyrolysis,” Roger Knight said.

“Industries such as timber production or agriculture are left with byproducts such as sawdust, crop stalks, or manure which can be modified into a charcoal form and mixed with other components to create compost,” Mr Knight said.

“Assessments by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has estimated that biochar could mitigate up to 6.6 billion tonnes of CO2 globally by 2050, so the impact could be enormous and there is a growing interest in researching its potential,” he said.

“The production of biochar could be huge for agriculture; by reducing a farmer’s need to employ inorganic fertilisers and improving soil health such as in water retention, aeration, and carbon sequestration.”

“As water becomes an increasingly variable resource, biochar could play an important role in providing water savings. For every 1 percent you increase the soil carbon through using biochar, you increase the water holding capacity of your land by 10 to 30 tonnes per hectare,” Roger Knight said.

“So not only are you reducing your emissions, you’re also saving time, money, and water,” Mr Knight said.

The project started from the ground-up and was a wholly community-led venture across the southern Murray-Darling Basin following a co-design process in which communities identified areas of interest for future research; including biochar.

“We wanted to explore whether there was a community interest in the production of biochar, and how a production industry could be created, as well as investigating potential barriers,” Roger Knight said.

“We began by building a regional network across 26 different entities through the Murray-Darling Basin Economic Diversification Program, which involved four cluster groups meetings across 45 attendees, where 26 industries and businesses attended,” Mr Knight said.

“We brought on experts such as ANZ Biochar to facilitate some information exchange on the quantification of waste streams, the process of pyrolysis, and the benefits and ongoing research into biochar,” he said.

“I also attended a trial site in South Australia to learn first-hand how other organisations, such as Landscapes SA, are trialling biochar on farms, alongside also learning how to make biochar using a cone kiln by not for profit group Maccy Biochar.”

“All-in-all this was a co-design process that involved government agencies, timber producers, farmers, manufacturers, researchers, and First Nations – such as representatives of Moama Local Aboriginal Land Council,” Roger Knight said.

“The community had heard of the benefits it posed, such as nutrient transfer and improving productivity; and they wanted to learn more and consider production and trial options in the future,” Roger Knight said.

“This network helped us identify the necessary industry connections needed to establish a biochar industry, where co-benefits could be made, and what barriers might exist for end users and producers,” Mr Knight said.

“The subsequent network we had built was an extremely useful outcome as well. It opened opportunities for other collaborations, such as employing local First Nations people to assess how both timber byproducts and natural fallen timber are causing environmental issues and to determine its potential as feedstock for biochar production to reduce the impact on environmental areas,” he said.

“These timber by-products have a variety of other uses with First Nations people and can be adapted as a fuel source or burnt in cultural burning. This would also have the added benefit of avoiding log jams blocking waterways and affecting flood plain dynamics, while also protecting cultural sites.”

Roger Knight hopes that the networks built on funding from the One Basin CRC can lead to creating bespoke products to suit a range of end-user needs, through trial work and research assistance.

Some of these needs could include feasibility of processing different biomass feedstocks, such as rice straw, testing and optimising production processes, and mixes with composts, livestock feed additive to reduce methane emissions, and more.

To achieve this, the project team need to trial soil types, biochar products, lease or purchase pyrolysis equipment, and explore how a biochar industry could be established in regional Australia.

“We’ve started the first phase by building the initial network across the Southern Basin, thanks to the CRC and program funding. Now, we’re hoping to research this further and investigate the adaptive benefits, like testing across different soil types, environments, and industries, and commencing a production trial,” Roger Knight said.

“What’s great about this project is that it’s not someone telling communities they need to adopt it. This has been community-led from the beginning,” Mr Knight said.

“This partnership is an example of how these connections link across a spectrum of industries and interests to achieve something positive for the whole region,” he said.

“The research we have been conducting wouldn’t have been possible without the consortium of interests working together and finding ways to trial this innovation in future iterations of this project.”

Goondiwindi Regional Hub Manager Marti Beeston echoed the boosts to communities, highlighting the important role this collaboration holds within the CRC.

“Place-based research undertaken in collaboration – not just consultation – with industry is a core theme in how the CRC operates,” Marti Beeston said.

“The biochar project is yet another example that building relationships in the community is a practice that pays off and only strengthens the quality of research and outcomes,” Ms Beeston said.

“Conducting research in our regional southern Basin communities is also special. Having partners engage in these areas outside of capital cities supports the regions to build new economies and develop critical industries from manufacturing to agriculture,” she said.

“This project is only the start of the collaboration we have across almost 90 partners; and growing. We’re excited for the future and continuing to strengthen these partnerships between industries and researchers.”